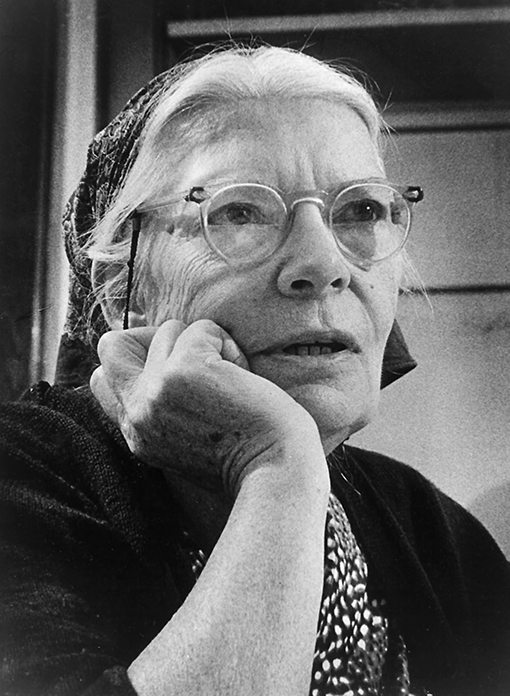

Dorothy Day is one of four Americans that Pope Francis held up as worthy of imitation in his 2015 address to Congress. Her example has inspired thousands of adults—Catholic and otherwise—to carry on her commitment to the corporeal Works of Mercy, peace, and social justice.

But Dorothy Day can be a good model for kids, too. Over the past year, I’ve been working on a children’s picture book about Dorothy Day’s childhood experience of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake (Dorothy Day and the Great Quake). As I researched her childhood, I was struck by how much her early experience either foreshadowed her later work, or planted the seeds for it.

To help you introduce your kids to this saint-on-the-way (the formal process for her canonization is ongoing), I’d like to share a brief sketch of her life—including some interesting details of her childhood. Then I’ll suggest a list of five themes kids can learn from Dorothy Day. And at the end of this article, you’ll find a story this future journalist wrote for the Chicago Daily Tribune when she was 13 years old.

Her Childhood and Life

Servant of God Dorothy Day is best known as the co-founder(with Peter Maurin) of the Catholic Worker Movement, which the two started in 1933 to inform workers about the social teaching of the Catholic Church and to promote the Works of Mercy. Their aim was to encourage Christians to take personal responsibility for living out the Gospel in order to “create a world where it is easier to be good,” as Peter later put it.

Dorothy was born in Brooklyn, New York, on November 8, 1897.She was the middle child of five children in a family that moved around quite alot, from Brooklyn to the San Francisco Bay area, to Chicago, and then back to New York. Her father was a sports journalist and her mother a homemaker.

Dorothy was a very spirited girl who loved nature and playing outdoors, imaginary games, reading, and writing little stories. She also had a temper that sometimes got her into trouble. She and her younger sister Della were best friends all their lives, and she was always very close to her mother.

Although her parents were not religious, Dorothy was aware of God from a young age. Once she picked up a Bible, and as she read from it, she felt she was in touch with something very holy—that she was being introduced to God.

As a child she went with some neighbors to church for a little while, and later, as a teenager, she was baptized and confirmed in the Episcopal church. But she wandered away from church and did not embrace faith in a wholehearted way until much later.

All her life, Dorothy loved the natural world. As a little girl, she could immerse herself for hours exploring birds’ nests, creating dolls from calla lilies (with a rosebud for the head), looking for shells at the beach, watching anthills and gopher holes, and making perfume from crushed flowers.

But she also loved just running around with the kids in the neighborhood after dark, having a good time. And she could be feisty! When her brothers teased her, she would fight back. She was always standing up for what she believed was right, and that caused problems sometimes.

Curious and precocious, Dorothy was a passionate reader,especially of adventure stories, and became quite a storyteller, too. She wrote stories for Della on pink notebook paper, then read them to her at night. At age thirteen, she even had some of her stories and poems published in the Chicago Daily Tribune—a preview of her lifelong work as a writer and journalist.

When the terrible earthquake of 1906 devastated San Francisco, Dorothy and her family were living across the bay in Oakland. When refugees traveled from San Francisco to Oakland seeking shelter and food, her mother and their neighbors worked day and night to help them, setting up a soup kitchen, putting up tents, and offering every spare piece of clothing they had.

This outpouring of loving community for those in need left a deep impression on eight-year-old Dorothy. We might even say it was the seed for the Catholic Worker Movement. As a young woman, over and over Dorothy asked herself, “Why? Why can’t the world be just and caring so that everyone can have enough?”

She wrote much later in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness:

I wanted everyone to be kind. I wanted every home to be open to the lame, the halt and the blind, the way it had been after the San Francisco earthquake. Only then did people really live, really love their brothers [and sisters].

As a young woman, her compassion for others found an outlet in her work as a journalist for Socialist newspapers and magazines, for which she wrote articles documenting the lives of the poor. She ran in New York literary circles, becoming close to Eugene O’Neill, whose influence she later said heightened her religious sensibilities. As a young activist, she participated in marches for workers’ rights and for the right of women to vote. A love affair with a prominent member of the Communist Party ended badly and resulted in an abortion that she deeply regretted later in life. She was briefly married, then divorced, during this tumultuous part of her life.

Throughout her young adult years, Dorothy flirted with Catholicism, but it wasn’t until she learned she was going to have a baby with her common-law husband that she finally made the leap. She felt so grateful to God for this gift that she decided to have her little girl, Tamar, baptized in the Catholic Church; Dorothy herself was baptized a Catholic in 1927.

After her conversion, she left behind her old life and associations. But she still burned with a passion for justice, especially when it came to helping the poor. For several years, she prayed to discover a way to combine her new faith, her journalism, and her love for the poor.

God answered her prayers when she met Peter Maurin, an eccentric (some would say saintly) former Christian Brother who knew all about the Catholic Church’s teachings on social justice. Together they launched a newspaper, The Catholic Worker, distributing it in New York City’s Union Square for a penny a copy on May 1, 1933, in the middle of a massive rally of communists. The paper was intended to offer workers a Christian alternative to the Communist Party.

“It’s time there was a Catholic paper printed for the unemployed,” an editorial in that first issue explained. “The fundamental aim of most radical sheets is the conversion of its readers to radicalism and atheism. Is it not possible to be radical and not atheist? Is it not possible to protest, to expose, to complain, to point out abuses and demand reforms without desiring the overthrow of religion? In an attempt to popularize and make known the encyclicals of the Popes in regard to social justice and the program put forth by the Church for the ‘reconstruction of the social order,’ this news sheet, The Catholic Worker, is started.”

Soon after publishing that first issue, Dorothy and Peter and their collaborators started a soup kitchen, which was quickly followed by a“house of hospitality” for those in need of shelter.

Many more houses of hospitality and offshoots of the newspaper were established over the following decades as the newspaper gave birth to a broad-based, loosely organized lay movement. When “Catholic Workers” advocated for peace and social justice, they did so not as armchair activists, but as Christians who were personally involved in doing the Works of Mercy, often at a significant personal sacrifice.

For her part, Dorothy spent the rest of her life writing for The Catholic Worker, visiting various Catholic Worker houses of hospitality, and living intimately with the poor in the movement’s first house of hospitality in New York City. And she continued her work on behalf of social justice—but this time, her efforts were deeply rooted in her faith, confounding traditional political categories. The same Christian personalism that led her to march for workers’ rights and live in solidarity with the poor also led her to oppose government welfare programs (on the grounds that they subverted every person’s responsibility to care for one another). The same regard for human dignity that led her to be an early advocate of civil rights also prompted her to condemn abortion and birth control as a form of “genocide” aimed at black and Hispanic Americans.

And while she challenged unjust authority throughout her life, she respected the authority of the Church. She told the Harvard psychologist Robert Coles: “I love the Church with all my heart and soul. I have never wanted to challenge the Church, only be part of it, obey it and in return receive its mercy and love, the mercy and love of Jesus.” (That did not stop her from quietly challenging the Church to do the right thing, as in 1963 when she joined a group of women who fasted for ten days outside the Second Vatican Council in the hope that the bishops would condemn all war.)

Through it all, she found strength and solace in her Catholic faith, regularly praying the rosary and attending daily Mass. She once wrote this prayer in her diary: “I believe You are a personal God, and hear me when I speak, even my trivial petty speech. So I will tell You personally over and over I love You, I adore You, I worship You. Make me mean it in my life. Make me show it by my choices. Make me show it from my waking thought to my sleeping” (August 21, 1952).

Dorothy died on Nov. 29, 1980, but her Catholic Worker Movement lives on today. About 200 Catholic Worker houses serve people and advocate for peace and justice in fifteen countries. The Vatican declared her a “Servant of God” in 2000—the first official step on the way to being canonized a saint.

What parents can learn from Dorothy Day

If there is one lesson parents can take from the life of Dorothy Day, it’s the importance of personal example.

Dorothy learned about kindness and compassion from her mother, whose actions at the time of the earthquake spoke powerfully to the child of the way the world ought to be all the time. Parents never fully know how their own actions may be the seeds of their children’s vocation, and even sainthood!

And while Dorothy’s parents did not provide her with an example of faith, many others throughout her life supplied that want, gently nudging her toward God. As a child, her Methodist next-door neighbors took her to services with them, and as a young woman, she once had three devoutly Catholic roommates who attended Mass and made time for personal prayer. Her friend Eugene O’Neill read her his poem, “The Hound of Heaven” and engaged her in conversations that deepened her religious sensibilities. And even during her radical activist days, she would occasionally drop into a Catholic church, where the attitude of the worshipers inside spoke to her heart.

We can explain the faith to our children as much as we want, but ultimately it is our example that matters.

What kids can learn from Dorothy Day

As you share Dorothy’s story with your kids (editing for age appropriateness!), here are five themes to point out.

- The importance of living the Works of Mercy. Do your kids know what the Works of Mercy are, and why they are central to the Christian life? Some Christians talk about the Works of Mercy from the comfort of their armchairs; Dorothy, on the other hand, literally lived with the poor, and advocated for Christian families to open their own homes to those in need. And as she continually reminded her readers, the point of the Works of Mercy is not just to help those in need, but to grow in holiness by the real practice of sacrificial generosity.

- Personal responsibility. Caring for one’s neighbor is not primarily the responsibility of the government, a charitable organization, or a faceless bureaucracy, but the personal responsibility of each and every Christian. Have your kids started to develop the habit of taking personal responsibility for putting things right, whether in your household or out in the world?

- Christ belongs to no political party. Your family may be Republicans, Democrats, or members of the American Solidarity Party—but do your kids know that following Christ ultimately means transcending tribal and partisan affiliations? Dorothy Day and other Catholic saints went wherever truth, love, and justice took them—no matter what feathers that ruffled.

- Action is powered by prayer, and prayer is deepened by action. “With prayer, one can go on cheerfully and even happily,” Dorothy once wrote. “Without prayer, how grim a journey!” Over and over, she showed in her words and her life that it is the deep well of faith that makes action on behalf of justice fruitful. But while she left behind the atheistic activism of her youth, she also openly criticized Christians who went to church and prayed at home but failed to act for justice in the world. Do your kids pray about their day? Do their prayers shape their actions, especially toward those in need? You can begin to help them link prayer and action by teaching them how to pray a daily examen, in which one reflects on and prays over one’s actions throughout the day.

- The power of imagination to build a Civilization of Love. As a child,Dorothy loved reading and telling imaginative stories—a passion she never completely gave up. That imagination—the ability to ask, “What if…?”—enabled her to envision a world in which people truly loved and cared for one another. She used her writing talent to share that vision with others…and to inspire them to act to fashion a true Civilization of Love. Do your kids know how to imagine?Are their dreams fueled by Christian values and stories? Do you help them turn their Spirit-inspired dreams into reality—or do you tend to crush them with “realism” that is really atheistic fatalism in disguise?

And perhaps that last point makes for a good transition to an example of Dorothy’s earliest writing. One of several items published in the Chicago Daily Mail in 1910 and 1911, it’s difficult to know how the mature Dorothy Day would have judged the parable; but in any case, it offers a glimpse into a child who already dreamed of a world of goodness and justice.

A Bird Story

by Dorothy Day (age 13), Chicago Daily Tribune September 3, 1911, page H2

A bird family had a nest in the top of an elm tree. Four speckled little eggs lay in this nest until one happy day came when there were four chirping little mouths to feed. Then the bird mamma and papa were very happy. But one sad day when the parents came home from worm finding the nest was empty and the poor birds almost gave way to tears. But they decided to fly at once to the fairy queen and ask her what had become of their little ones. If she could not find them she could at least punish the one who stole or killed them.

So they flew, never pausing until they reached the house in which the queen dwelt.She greeted her friends kindly, and, on hearing the sad misfortune, agreed to help them. She sent elfin spies out into the world to search for the culprit.The elves found the naughty boy who stole the birds and made him bring them to the father and mother, even dead as they were. The parents wept bitter tears at the sight of the dead birdlings and the fairy queen, moved at their grief, gave the parent’s tears the power of bringing the babies to life. The mamma and papa birds, unwilling to live again in the cruel world, built a nest in fairyland and lived happily there ever after.

The naughty boy cried and wanted to go home, so the elves, instead of punishing him as they intended to do, made him promise never to harm the birds or any other living creature. He willingly promised this and the elves brought him home, a better boy for the lesson he had learned.

Learn more

Videos

Websites

Dorothy Day

Read an introduction to her life and spirituality and search much of her writing at Catholicworker.org.

Excerpts from the Writings of Dorothy Day

From the website of Jim and Nancy Forest.

The Dorothy Day Guild

Follow news of the canonization process.