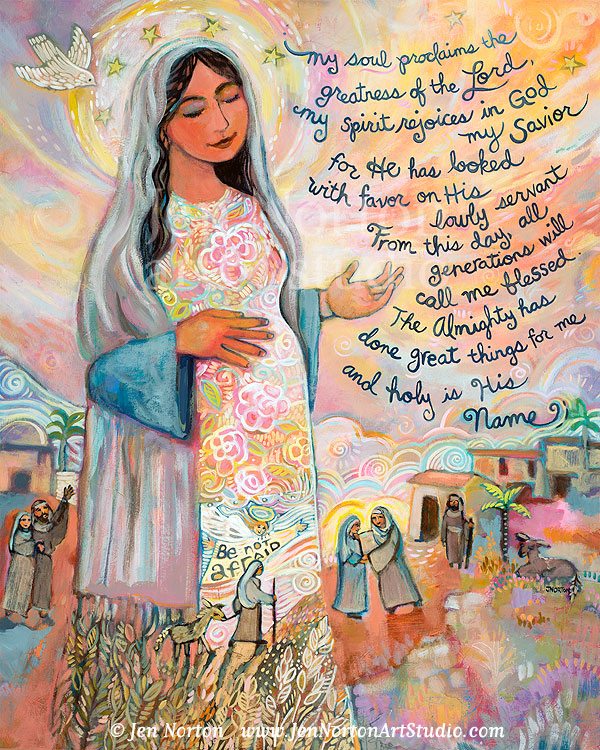

One of my favorite pieces in the new Illuminated Rosary book The Joyful Mysteries is Jen Norton’s Magnificat. I love this piece not just because the artist does such a wonderful job of capturing the joy and hope of the song that the Gospel of Luke places on Mary’s lips (1:42-55), but also very simply because I love the Magnificat, and there is precious little art depicting it. In fact, when I was looking for art of the Magnificat during my research for the book, the only usable example I found was James Tissot’s The Magnificat. So I e-mailed Jen Norton, whose gorgeous Hail Mary had caught my eye earlier. “Do you think you’ve got a Magnificat in you? Because the world is apparently in short supply of Magnificat paintings.” To my delight, she agreed to take on the project, and the result is a warm, vibrant piece that celebrates, with Mary, God’s saving work in human history.

Why, in a world absolutely awash in Marian art, are depictions of the Magnificat so rare? It seems strange, given that the canticle is the longest speech that the Bible attributes to Mary, and that Luke uses it to place the rest of the Gospel in a larger context. But then, the Magnificat doesn’t exactly make the top ten list of Marian prayers and devotions, does it? We Catholics pray the Hail Mary, the Hail Holy Queen, the Regina Caeli, the Angelus, the Litany of Loretto, and the Memorare—but the humble Magnificat? Not really, not unless you pray the Liturgy of the Hours. (And how many of us do, despite the Church’s repeated invitation for the laity to take up the practice? But that is a different essay).

One of the reasons I wanted to include the Magnificat at the beginning of the Illuminated Rosary books was to gently propose that the Song of Mary ought to have a more prominent place in our prayer lives, right up there with the Our Father and the Glory Be. Our own family has been working on memorizing the Magnificat (slowly, slowly) by sometimes using it as our evening prayer, and also by praying it before we pray the rosary.

Why does the Magnificat deserve to be prayed more frequently by those of us in the pews? Let me propose four reasons:

- The Magnificat is the first prayer of the Church, and our prayer, too.

- The Magnificat calls us to recognize God’s saving work in our lives.

- The Magnificat teaches us the true meaning of humility.

- The Magnificat invites us to give birth to Christ.

The Magnificat is the first prayer of the Church, and our prayer, too.

A good starting point for a deeper appreciation of the Song of Mary is simply recognizing that it can be (and should be) our song, too.

The Magnificat might rightly be called the first prayer of the Church, in the sense that it is spoken by Mary, who is the mother of the Church.

The Magnificat might rightly be called the first prayer of the Church, in the sense that it is spoken by Mary, who is the mother of the Church. She is the mother of the Church not only because Jesus gave her this role (John 19:26-27), but because the Church found its beginnings in her perfect assent to God’s will—her fiat, her “let it be” (Luke 1:38). So the Catechism can say that the Canticle of Mary “is the song both of the Mother of God and of the Church; the song of the Daughter of Zion and of the new People of God” (Catechism #2619).

If the Magnficat is the prayer of the Church, then it is our prayer; and if it is our prayer, then Mary’s words become our words, and praying those words helps us to respond to God as she did.

The Magnificat calls us to recognize God’s saving work in our lives.

Gratitude, a foundational virtue for the spiritual life, is best nurtured by learning to recognize God’s gifts in our lives, and praying the Magnificat can help us in that direction.

A big chunk of Mary’s song is given over to recalling all the ways God has worked in human history. Pope Benedict says that the Canticle of Mary names a series of seven ways that God has repeatedly acted in human history: “He has shown strength . . . he has scattered the proud . . . he has put down the mighty [from their thrones] . . . he has exalted those of low degree . . . he has filled the hungry with good things . . . the rich he has sent empty away . . . he has helped . . . Israel” (Pope Benedict, General Audience, 15 February 2006, #3).

The Magnificat recalls God’s saving work in order to announce that all those actions have now reached their definitive conclusion, and the promises made to Abraham and his children have been fulfilled, in the event of the Incarnation of the Son of God.

Because the Incarnation is extended through the sacraments (particularly the Eucharist), the seven saving acts of God described in the Magnificat also apply to our own lives today. As we pray the Magnificat, then, we are not just praising God for what he has accomplished in the past, but for all the ways in which he acts in our lives today. The Magnificat prompts us to ask: How is God showing his strength in my life today? How is he scattering the proud? How is he casting down the mighty from their thrones? Ho is he exalting the lowly, filling the hungry with good things, and sending the rich away empty? And how is he helping his people? How is he helping me?

This miniature Examen leads us to respond to God’s work just as Mary does, with humility.

The Magnificat teaches us the true meaning of humility

I don’t know about you, but Mary’s litany of all that God does to the proud, the rich, and the mighty has always made me a little uncomfortable—maybe because it is so openly judgmental that it feels impolite (here in Minnesota, we just don’t talk that way about people . . . at least not publicly). Or maybe because the prospect of turning the social order inside out is a little unsettling.

Or maybe it makes me feel uncomfortable just because I recognize all of those things in myself.

The rebuke of the proud, the rich, and the powerful that we find in Mary’s song shouldn’t shock us; after all, it only repeats what the prophets had been saying for millennia, and foreshadows the message of Jesus. If the Magnifcat makes us uncomfortable, all the more reason to recite it regularly; we need to be made uncomfortable.

More to the point, we need to be made humble. Humility is the great theme of the Magnificat, not to mention the hinge on which Mary’s story turns.

People sometimes balk at the idea of humility; it tends to rub our individualistic, egocentric culture the wrong way. In fairness, though, some of that resistance can be traced back to a false idea of humility as a quiet yielding to human power. By that definition, humility becomes concerning when it diminishes and silences the poor and the lowly—especially when oppression and violence are involved. Too often, women and their children have suffered as a result of such oppression and violence, leading some to object that the humility of Mary makes a poor model.

But if Mary teaches us anything in her song, she teaches us what it means to be truly humble. While a yielding spirit is key to her humility, it is abundantly clear that she is not yielding to any human power—far from it. Rather, she is yielding to the God of love, the God of truth, the God of life, and that makes all the difference. Look at the very words that open the prayer: “My soul magnifies the Lord,” Mary says, sometimes translated as, “My soul glorifies the Lord,” or, “My soul proclaims the greatness of the Lord.” Pope Benedict XVI writes insightfully about the significance of these words:

Mary wanted God to be great in the world, great in her life and present among us all. She was not afraid that God might be a “rival” in our life, that with his greatness he might encroach on our freedom, our vital space. She knew that if God is great, we too are great. Our life is not oppressed but raised and expanded: it is precisely then that it becomes great in the splendour of God.

The fact that our first parents thought the contrary was the core of original sin. They feared that if God were too great, he would take something away from their life. They thought that they could set God aside to make room for themselves. (Homily, Monday 15 August 2005)

Mary’s receptive, open stance toward God allows “divine grace” to “burst into . . . [her] heart and life” (General Audience, #2); and that makes all the difference. The portrait of Mary painted by the Magnificat is not of a woman diminished and silenced, but of a woman loudly (maybe even a little raucously!) proclaiming the victory of God—and through him, the victory of all who, like her, are little or lowly in the sight of humans. Her whole song is fairly shot through with praise, thanksgiving, joy, and hope. “From this day all generations will call me blessed,” she sings. Why will all generations call her blessed? Because “the Almighty has done great things for me, and holy is his Name.” It is God’s work in her that exalts her, and leads all generations to call her blessed.

This isn’t your China-doll Mary, people.

The mighty are cast down from their thrones and the rich sent away empty not out of retribution or revenge, but because they (and “they” is all of us) need to be made humble.

Understanding humility in this way casts in a new light Mary’s unsettling words about the fate of the proud, ruch, and mighty. The proud are scattered, the mighty are cast down from their thrones, and the rich sent away empty not out of retribution or revenge, but because they (and “they” is all of us) need to be made humble. For it is only in adopting Mary’s receptive, open stance toward God that we make room to receive God in ourselves. This is why the humble will be exalted: their “emptiness” leaves room for divine grace to burst into their hearts and lives. And when we allow God to enter our hearts and lives, we are “raised and expanded,” and we become “great . . . in the splendor of God.”

The Magnificat invites us to “give birth” to Christ in our lives.

So, what does it mean for us to become “great in the splendor of God”? If Mary is our template, then it means nothing less than to give birth to Christ. Pope Benedict attributes this insight to St. Ambrose: “If, according to the flesh, the Mother of Christ is one alone,” St. Ambrose wrote, “according to the faith all souls bring forth Christ; each, in fact, welcomes the Word of God within.”

In other words, we are all called to “give birth” to Christ in our lives. As Pope Benedict says, “Not only must we carry him in our hearts, but we must bring him to the world, so that we too can bring forth Christ for our epoch” (Audience, #4).

Isn’t this the essence of our Christian identity, to humbly make room for Christ not only in our souls, but in our very bodies? (Mary might also have something to teach us about the embodiment of Christian discipleship in the kenosis of her pregnancy.) Isn’t this why we receive Christ in the sacraments, especially baptism and the Eucharist: to put on Christ, to become, corporately, the Body of Christ in the world today?

~ ~ ~

And that, my friends, is why I love the Magnificat, and why I think it would be would great to hear it recited with the rosary more often. It is a prayer that challenges us with the paradox of an exalted humility. It is an eschatological prayer, utterly confident in God’s ultimate victory, and that makes it a prayer for rejoicing. It is a prayer to be sung rather than said, a prayer to be shouted out rather than whispered.

The Song of Mary demands a little extra of our prayer because it is the song of one who has happily abandoned herself to God. Why not try it? Because if Mary could do it, so can we.

Prints of Jen Norton’s Magnificat are available at her website, JenNortonArtStudio.com.